XSS, SQL injection, XMLrpc – when a WordPress security update is released, the update reports contain mainly cryptic abbreviations. Even if it is clear that these updates are necessary and the added security is very pleasing, it is important to understand what is behind these security gaps. Because only if you understand which gaps the updates close can you make an informed decision. That’s why we’re focussing today on cross-site scripting, or XSS, which is by far the most common complex attack on WordPress websites.

Hacker attacks can be compared to a burglary. Brute force attacks are more similar to the crowbar method. Criminals keep using the tool until the door or window breaks open. Attacks on XSS vulnerabilities, on the other hand, are sophisticated: The criminals know exactly where to start and gain targeted access to a website.

Cross-site scripting involves the targeted exploitation of security vulnerabilities in websites. This involves injecting malicious scripts into a trustworthy context (your website!). Similar to a stowaway on a ship, this malicious code uses your website as a vehicle to pursue its own goals.

In the worst-case scenario, confidential information or even access to the victimised user’s computer is obtained. Such attacks are not exactly rare: A good half of the vulnerabilities found in plugins by security provider Wordfence in 2015 and 2016 were cross-site scripting vulnerabilities. An XSS attack often forms the “basis” for further attacks, such as spam, phishing or even DDoS attacks. That’s why today I’m going to show you exactly how cross-site scripting works, what types of attacks there are and how dangerous the attacks are.

Cross site scripting has a basic principle

Cross-site scripting works on the basic principle of exploiting a loophole and injecting malicious code into your website. It is always a danger when a web application forwards entered data to the web browser without checking for any existing script code. A vivid example of such a web application is a support chat.

The malicious scripts can reach the server via the web application itself. From there, the malicious code sooner or later ends up on the affected clients. A good example of such an XSS vulnerability is the bug discovered in July 2016 in the image meta info in WooCommerce 2.6.2. A bug made it possible to inject HTML code into the meta descriptions of images from outside. Any device on which the affected image was viewed more closely (e.g. by clicking on the image) would run the risk of being attacked. For example, the computers on which this image was viewed could have been infected with a virus.

Subscribe to the Raidboxes newsletter!

We share the latest WordPress insights, business tips, and more with you once a month.

"*" indicates required fields

Popular trick in cross-site scripting: manipulated forms

XSS can also make it possible to replace harmless forms with manipulated forms. These forms then collect the victims’ data (on your website!). Incidentally, even SSL encryption cannot protect against this. HTTPS “only” means that the connection between server and client is encrypted. However, if the form itself is manipulated, even an encrypted connection is useless.

As with other types of attack, the goal in most cases is monetisation. In concrete terms, this means that either data is stolen and later sold, or infected websites are integrated into a so-called botnet, which is then rented out.

3 types of XSS

Cross-site scripting attacks can be roughly divided into three types:

- reflected cross-site scripting

- persistent cross-site scripting

- DOM-based or local cross-site scripting

Roughly speaking, XSS attacks work as follows: Malicious code is injected where input from the client is expected (for example, in an internal page search). As part of the server’s response, the malicious code is then executed on the client, i.e. in the browser. And this is exactly where the damage is done, e.g. data is stolen.

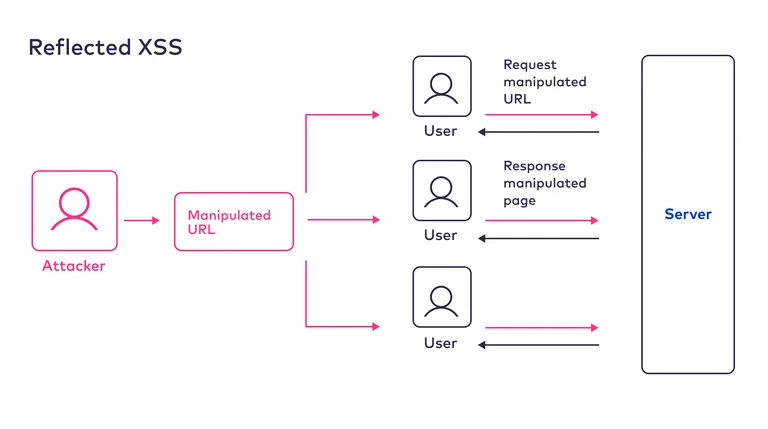

Reflective cross-site scripting

Some entries, such as search queries, are reflected by the server. This means, for example, that the website displays “You searched for test” after entering “test” in the search field. The text entered therefore becomes part of the server’s response.

This is precisely what is skilfully exploited: If a malicious script is sent to the web server instead of a search term, the website can be manipulated so that it ultimately executes it. This type of attack is also known as non-persistent. This means that the malicious code is only temporarily injected into the website in question, but is not saved.

In July 2017, such a vulnerability was found in the WP Statistics plugin (and fixed on the same day!). An input value on the page ‘wps_visitors_page’ was forwarded unchecked, which led to a vulnerability due to reflected XSS. This meant that a website could be hacked if an admin had previously clicked on a correspondingly manipulated link.

It works like this: links with manipulated parameters are distributed to potential victims. Without realising it, the victim sends a “manipulated” request to the server by clicking on the link, and the malicious code is executed together with the server’s response. As the code – unlike persistent XSS – is not stored anywhere, it has to be distributed en masse to potential victims. This can happen via emails or social networks, for example.

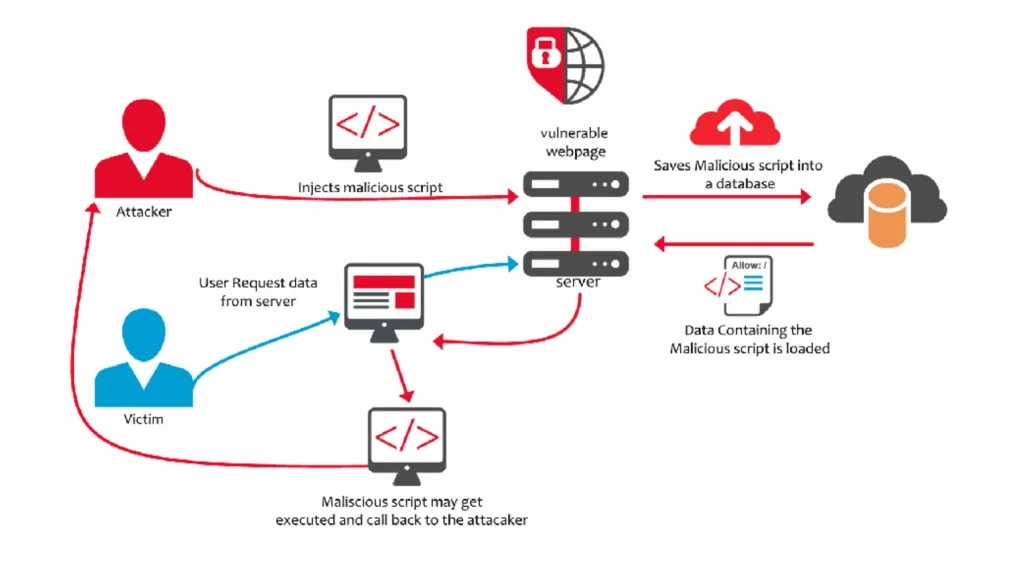

Persistent Cross Site Scripting

With persistent XSS, the malicious scripts are stored on the web server and delivered each time they are called up by a client. Predestined for this are web applications that store user data on the server and then output it without checking or coding (including forums). This type of scripting can be particularly dangerous for highly frequented blogs and forums, as the malware can spread quickly due to the large number of users.

Example: Posts made in a forum are stored in a database. These are often stored unchecked and unencrypted. This opportunity is often exploited and allows a malicious script to be added to a normal forum post (simply by adding a comment). Users either receive the link to the post by email or arrive at the corresponding entry by chance and execute the script when they access the post. Now, for example, affected clients could be “spied on” or added to a botnet for further attacks.

WordPress hosting management

With our Raidboxes dashboard, you get a seamless, intuitive interface that makes managing your WordPress sites easier, faster, and more efficient. Check it out!

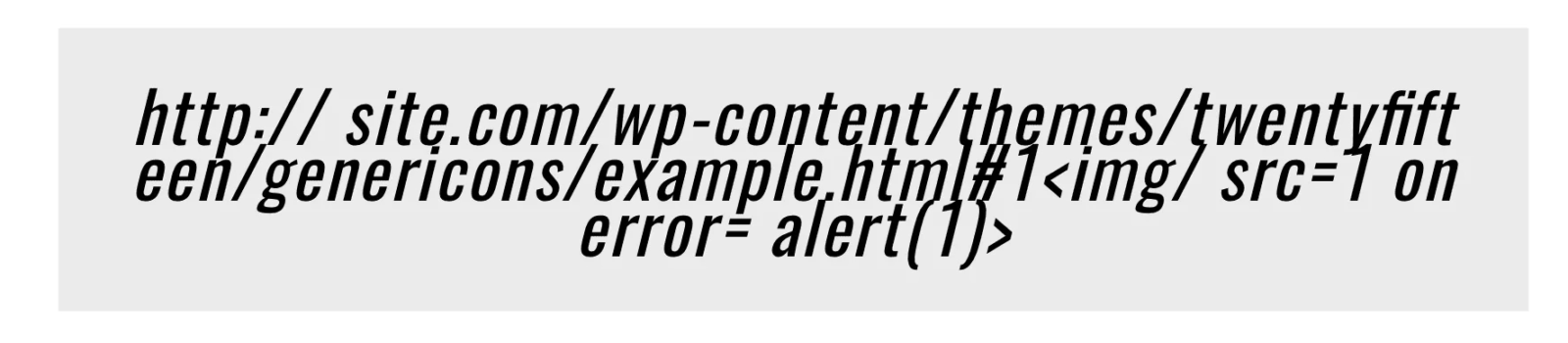

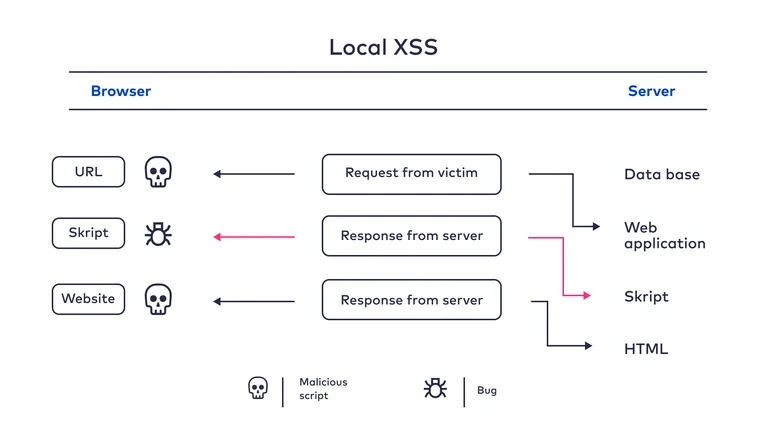

DOM-based or local cross-site scripting

Unlike persistent and reflected XSS, DOM (Document Object Model) based cross-site scripting works by executing client-side scripts. This means that the server is unaware of such an attack and server-side security measures do not help.

A well-known example of such a gap was the case of the genericon package. The genericon package is an icon set that is used by many plugins. It was possible to inject malicious code via an HTML file in this icon set.

However, the prerequisite for a DOM-based XSS attack is that users click on a manipulated URL. By calling up this URL, the malicious code can be executed through a gap in a client-side script. Among other things, the fact that a link must first be clicked on makes DOM-based XSS a somewhat more difficult and therefore less likely type of attack.

Example: The manipulated URL is clicked and sends a request to the web application. This responds by passing the script code (which is faulty but not manipulated) to the browser in order to start the execution of the script there. The manipulated parameters from the URL are now interpreted in the client’s browser as part of the script and executed. The website displayed in the browser is thus changed and users now see the manipulated website – without realising it.

Measures against cross-site scripting

The best measures against cross-site scripting attacks are easy to implement. It is best to rely on regular updates, firewalls and whitelists. Secondly, the output of the server can also be secured.

Regular updates

The vulnerabilities through which the malicious code is infiltrated are located either in the WordPress core, in plugins or in themes. This is precisely why regular updates of all these components are so important. These updates fix the vulnerabilities that have been found to date.

It also makes sense to regularly read the details of updates to get a feel for which security vulnerabilities are regularly closed via the updates. For the maintenance and security updates of the WordPress core, this information is documented in the WordPress blog, for example.

Firewalls and whitelists against simple XSS attacks

Another simple protective measure against XSS attacks are so-called web application firewalls, or WAFs. These firewalls are the centrepiece of large security plugins and are fed with the latest vulnerabilities by the respective manufacturer’s research team. A WAF is generally a procedure that protects web applications from attacks via the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP).

However, these protection mechanisms also have their limits. This is because in some XSS attacks, the attack takes place via the database. Checking user input for malicious code is therefore one of the key security mechanisms in the fight against XSS attacks. For example, the content of comments is scanned for suspicious character strings and sorted out if necessary.

The data output should also be secured

Regular updates close existing XSS security gaps and firewalls and whitelists try to filter out malicious code before it reaches the web server and can infect the website. However, the data output should also be secured accordingly. Most programming and scripting languages, such as PHP, Perl or JavaScript, already have predefined functions for character substitution or masking. These ensure that “problematic” HTML meta characters such as <, > and & are replaced by harmless character references. This prevents the malicious code from becoming active. The code should also be cleaned up using sanitisation libraries. To do this, a plugin is installed on the server and additional code is integrated into the source code of your website. The following code snippet then ensures, for example, that is added to the permitted attributes:

var sanitizer = new HtmlSanitizer();

sanitizer.AllowedAttributes.Add("class");

var sanitized = sanitizer.Sanitize(html);Programming skills are required to implement this. This safeguarding of the data output is easy to implement for someone with this knowledge.

A healthy dose of scepticism: how users protect themselves

However, not only the website itself, but also the clients (i.e. your web browser) are affected by XSS attacks. Many XSS attacks can be prevented by being critical and careful when dealing with “foreign” links. One option is to use NoScript add-ons. These prevent the execution of scripts, i.e. the harmful lines of code that steal data, among other things.

If you want to be on the safe side, you can also prevent client-side cross-site scripting by simply switching off JavaScript support in the browser. If this so-called active scripting is deactivated, certain types of XSS attacks no longer stand a chance, as the malicious applications are not even started. However, most modern websites then no longer “work” properly – or, in the worst case, no longer work at all. It is therefore important to weigh up the aspects of security and usability. If you are interested in this option, you can find it in your browser settings.

Conclusion

XSS vulnerabilities are sometimes the most common gateways for malicious code. And a corresponding attack often forms the basis for further attacks, such as spam, phishing or even DDoS attacks. Your website is therefore hijacked and misused for other purposes. XSS is therefore not harmless, which is why appropriate protection is important.

Reflected and persistent XSS are particularly common, as local cross-site scripting is more complex and more difficult to implement. Websites that forward entered user data to the web browser without checking for any malicious code are particularly at risk. However, finding such gaps is not that easy. In principle, this is precisely the task of security providers such as sucuri and others, who are constantly developing their security measures.

But of course there is also a way for normal WordPress to protect itself from these attacks. Updating all WordPress components is a simple but very effective measure. If you keep your plugins and themes up to date and use a WAF, you’ve already taken a big step in the right direction. If you also use whitelists for incoming and outgoing code, you have already secured your website extremely well. However, the last two measures in particular are not easy to implement without programming knowledge.

Compared to the rather primitive brute force attacks, the more complex XSS attacks are unfortunately still relatively often successful. However, there are significantly fewer of these so-called complex attacks than there are brute force attacks on WordPress websites. Nevertheless, you should make it as difficult as possible for these attacks. After all, a successful hack not only costs time and money to remove the scripts, but can also jeopardise your position in search engines.

Leave a Reply